On writing a novel about adoption - Judith Trustman

The understanding of our human condition is often only as good as the rate of scientific progress. So our cultural norms would have us believe. As someone who worked within the legal system as a barrister concerned with facts and ‘proof’, I am often accused of being part of the problem- of being too concerned with evidence. But I like to ask people who have never set foot inside a courtroom, let alone one that deals with child protection and adoption orders: But don’t you realise, that courtrooms are also about stories? And it is true, but those stories are real, of human struggle, confusion, fear and also great courage in the face of adversity. They are deeply human stories, powerful stories, and irrespective of the outcome of a case, those stories are powerfully witnessed.

But stories can be manipulated, silenced, ignored as well. As an adoptee, I too experienced the feelings of confusion when the life I had before I was adopted was treated as if it had never existed. My adoptive mother said ‘but Judith, the life before you were adopted doesn’t count’. So too, the experience of my birth mother, who was told to ‘move on’, ‘go back to Ireland and say the baby died’. She was also, horrifyingly, taken to an unmarked grave where she was told I had been buried.

Many birth mothers and adoptees will have experienced some version of this. Over many years of representing birth mothers in court and knowing, first hand, the lifetime’s painful loss experienced by my own birth mother, it became very clear to me that whatever the circumstances may be of an adoption, after the child has been removed, the birth mother has to find a way to go on living. She will probably go on to live somewhere with someone, possibly have other children and yet, within the cover of a manila folder somewhere – our adoption records – she will have ceased to exist.

Adoption, in and of itself, is sadly sometimes a necessary arrangement. It can be a lifesaver too. It is not so much the why that it happens I take issue with, but it is the way it is done.There are also cultures in the world who have an entirely different form of adoption embedded within their culture. For example, in Inuit culture they have a form of adoption known as custom adoption. In some regions this tradition means that with nearly every nuclear family will have at least one adopted child. Sometimes called child sharing, it ensures that each child has a network of loving family and teachers throughout their lifespan plus their connections with birth family are maintained. In China there is a region where a practice known as ‘walking marriage’ means that the married couple do not live together and the child will be raised by the mother’s extended family with uncles acting as fatherly figures.

The point here is that there is no one size fits all when it comes to adoption and we could learn a lot from cultures, older than ours, who do not seem to practice the kind of secrecy and erasure that has been characteristic of modern systems of adoption. There are, even today, countries in which closed adoption still prevails.

Some adoption practice in the UK has improved, with social workers now tasked with creating a life story book for children who go on to be adopted. But it can only be a poor substitute for firsthand stories from the family of origin. My cousin, whom I came to know only a few years ago, will always find the time to tell me tales about my aunts, uncles, the gatherings, their behaviour, my grandfather’s standing in the village, in such a way that they have become stitched into the tapestry of my own memories.

Hilary Mantel, in her Reith lecture series was asked whether, in writing her imaginatively vivid accounts of Thomas Cromwell, she was conflating truth with fiction. Her answer, paraphrased here, was to describe a deathbed scene where the dying person is surrounded by six loved ones. That they are dying is fact, but at the moment of their death you will then have six different stories of that person’s life and their death. Mantel's key point was that "facts are not truth, though they are part of it".

Writing a novel has been a different kind of storytelling to the one seen in a courtroom. I have tried to use this powerful tool to bring to life the inner stories that will never find their way into a file, or a digitized record. And although the characters are fictional, stories made up, it is intended in its own way, to convey a form of truth, about our mothers, about us.

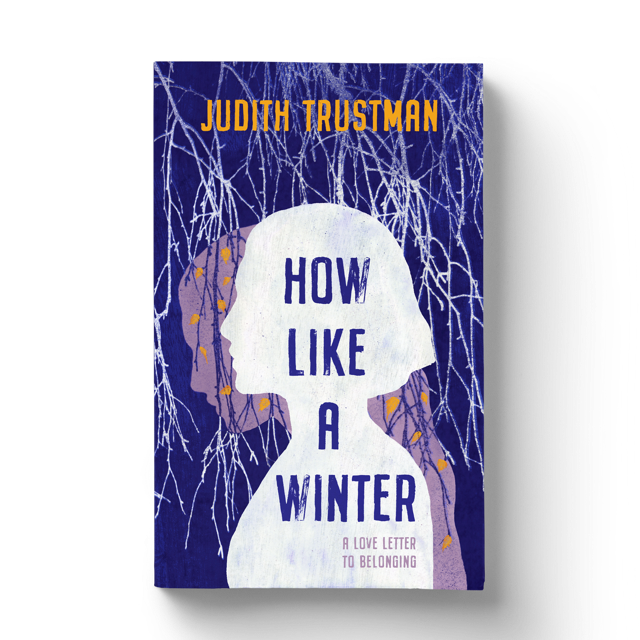

My book How Like A Winter, has a title borrowed shamelessly from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 97 ‘..how like a winter has my absence been from thee’. The novel is an attempt to give voice to those women who have to go on living after their child has gone. In writing it, I posed several questions: are you still a mother after your child has gone? Do the circumstances of your birth predict what you can become? And what about reunion, those who do/those who don’t?

I hope within the folds of the book to have given some dignity to the birth mothers and also put out there some versions of us, the adoptees, who have been told who to love and who not to love. When we come out of the fog, we take back what is ours, be that reunion, or the gems of truth we can find about our origins. Mine, those pearls of knowledge, I carry with pride.

I am grateful for the opportunity to connect with others like me and share some of the story of how I have tried to make our voices more heard.

Judith Trustman

https://judithtrustmanauthor.com/